A political savant and leader in policy and legislation, Donald Gainsborough is at the helm of Government Curated, where he deciphers the intricate dance between Washington D.C. and America’s industrial heartland. With car prices hitting historic highs despite administration claims of success, Gainsborough offers a sharp analysis of the current economic landscape. This conversation delves into the high-stakes messaging war over affordability, the complex realities of global supply chains under a tariff regime, and how automakers are navigating a minefield of competitive pressures and rising costs. We’ll explore why policies designed to reshore production are creating short-term pain for consumers and what metrics truly signal the health of the U.S. auto market.

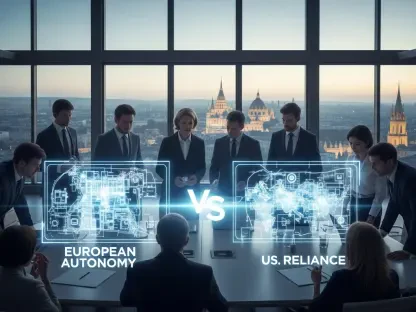

The average price for a new car recently hit a record high, yet some argue policies prevented an even worse outcome. How does this “it could have been worse” message typically land with voters facing affordability issues, and what specific examples could make that argument more compelling?

It’s an incredibly tough sell, and frankly, it often falls flat. When a family is staring down a sticker price that just hit a record of over $50,000, telling them it could have been another few thousand dollars higher doesn’t feel like a win. It feels like you’re disconnected from their reality. Voters feel the number on the price tag, not the hypothetical number that was avoided. To make that argument resonate, you have to shift the focus from a negative that was avoided to a tangible positive that was gained. For instance, instead of just saying “prices didn’t soar,” you’d need to be on the ground in Ohio or Michigan, pointing to a specific factory where a company like Stellantis is now investing its pledged $13 billion, and directly connect that to the tariff policy. You have to make it visceral, about American jobs and future security, not just abstract economic modeling.

In 2025, major automakers absorbed billions in tariff-related costs instead of passing them directly to consumers. What does this “wait-and-see” approach reveal about the auto industry’s competitive dynamics, and at what point does that financial pressure typically shift to the customer’s wallet?

That “wait-and-see” game tells you everything you need to know about how brutally competitive the U.S. auto market is. No one wanted to be the first to blink. Imagine you’re Ford, and these tariffs just added a billion dollars to your costs. Your first instinct isn’t to jack up the price of an F-150, because you’re looking right across the street at GM and Stellantis. If they hold their prices steady, you risk losing precious market share. So, everyone decided to “eat” the costs, taking a significant hit to their bottom line. The breaking point comes when the pain on the balance sheet outweighs the fear of losing customers. We’re hearing that 2026 is that point. With new models rolling out and sales projected to contract, the industry feels it has no choice but to start passing those billions in costs along. The pressure has built up, and the dam is about to break for the consumer.

Initial tariff adjustments made some imported cars cheaper to buy than cars assembled domestically with foreign parts. Could you walk us through the complexities of designing trade policies for such integrated supply chains and describe the typical unforeseen consequences for manufacturers and consumers?

It’s a perfect example of how a seemingly straightforward policy can become a tangled mess in the real world. The modern car isn’t built in one factory; it’s a global jigsaw puzzle. When the administration first slapped a 25 percent tariff on parts, it hit domestic automakers who rely on those global components hard. Then, they negotiated lower 15 percent tariffs for finished cars from places like the E.U. and Japan. Suddenly, you had this bizarre situation where a car built in Detroit was being taxed more heavily on its components than a fully assembled car rolling off a boat. It’s a classic unintended consequence. U.S. automakers were justifiably furious, as the policy was inadvertently penalizing them for building here. The administration had to scramble to fix it with a rebate system, but for a while, it created enormous uncertainty and frustration, demonstrating just how delicate and interconnected these supply chains truly are.

To offset high vehicle costs, the administration is promoting other measures like new tax deductions and relaxed fuel standards. How effective are these secondary policies at shaping public perception of affordability when the primary sticker price remains stubbornly high?

These secondary policies are like offering someone a discount on floor mats when they can’t afford the car itself. While a new tax deduction or the idea of saving money on gas over time is certainly helpful, it doesn’t solve the immediate, gut-punch feeling of that record-high sticker price. Voters are very direct; they know how much the car costs today. When they see a price tag of $50,326, a future tax break feels distant and abstract. As one strategist put it, voters appreciate the help, but many are savvy enough to think that these high prices could have been avoided in the first place without the tariff chaos. So while these measures might soften the blow for some, they do very little to change the headline narrative that cars are becoming increasingly unaffordable for the average American family.

The goal of reshoring auto production is a long-term project, but sales are projected to decline in 2026 amid rising prices. What key metrics will signal whether this tariff strategy is successfully balancing long-term industrial goals with short-term market health and consumer affordability?

This is the central tension of the whole strategy. We have to watch a few key indicators very closely. First, we need to see if those massive investment pledges, like the $13 billion from Stellantis and $10 billion from Toyota, translate into actual groundbreaking and hiring, not just press releases. That’s the long-term goal. Second, in the short-term, we must monitor the average transaction price. If it continues to climb well past the $50,326 mark while sales figures continue their projected decline, it’s a red flag that affordability is cracking and the market is unhealthy. The ideal balance would be seeing prices stabilize or even slightly decrease as domestic production efficiencies kick in, all while new factory jobs are being created. If we only see one without the other—either jobs at the cost of a collapsing consumer market, or a stable market with no new domestic investment—then the balancing act has failed.

What is your forecast for the U.S. new car market over the next 18 months?

The next 18 months look like a real nail-biter. The industry is bracing for a contraction in new vehicle sales in 2026, and I see no reason to doubt that. Automakers can’t absorb billions in tariff costs forever, so we are going to see those costs passed on to consumers in the form of higher sticker prices on new models. This will collide head-on with the affordability crisis that is already pricing many families out of the market. While sales were surprisingly strong in 2025, that was likely fueled by people rushing to buy before prices rose further. That demand is not sustainable. We’re heading for a period of turbulence where high prices will suppress demand, creating a tough, competitive environment for dealers and a frustrating one for anyone needing a new car.