With a deep background in policy and legislation, Donald Gainsborough, who leads the government affairs firm Government Curated, offers a sharp analysis of Florida’s embattled school choice voucher program. The system is currently under intense scrutiny following revelations of a $47 million budget shortfall and a state audit that uncovered hundreds of millions in unspent funds and a profound “absence of clear accountability.” Our conversation delves into the systemic breakdowns that led to this crisis, the practical implications for families, the legislative scramble to enact reforms, and the future of a program at a critical crossroads.

Given the $47 million shortfall from vouchers paid to students with unclear enrollment, what specific system failures allowed this to happen? Could you walk me through the typical verification process and explain where you believe the breakdown in accountability occurred?

The breakdown is absolutely systemic, stemming from what the audit rightly called an “absence of clear accountability.” A robust system would require verification before a single dollar is disbursed. Instead, it appears funds were paid out for 23,000 students based on an assumption of enrollment rather than concrete, real-time proof. The failure lies in the lack of a cross-checking mechanism between the Department of Education’s public school rolls and the private school enrollment lists held by the scholarship organizations. It feels like the right hand didn’t know what the left was doing, a glaring failure of stewardship that allowed tens of millions of dollars to flow out without anyone knowing for sure where these children were being educated.

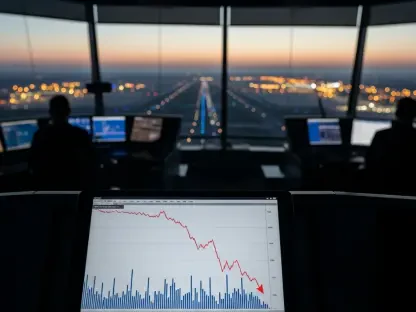

The state audit flagged over $400 million in unspent student funds as “potentially excessive.” From your perspective, why is such a large amount of money sitting dormant in these accounts, and what does this indicate about the program’s practical use by families?

Seeing over $400 million sitting unused is staggering and points to a major disconnect between the program’s design and its real-world application. For some families, especially those with special needs children, they may be saving for a larger, future expense—perhaps a specific therapy or a piece of adaptive technology. But for many others, it could indicate they find the system too complex to navigate or aren’t fully aware of what the funds can be used for. When auditors label that sum as “potentially excessive,” it’s a polite way of saying the state is allocating a massive amount of capital that isn’t actively being put toward education. It raises serious questions about whether the program is truly meeting the immediate needs of students or simply becoming a holding account.

Auditors found 299 special needs accounts illegally exceeded the $50,000 cap by a combined $2.3 million. How could this specific compliance rule be overlooked so many times, and what is the step-by-step process for clawing back those excess funds from individual accounts?

For 299 separate accounts to blow past a hard legal cap like $50,000, it signals a complete failure in automated monitoring. There should be a system in place that simply stops payments once an account hits that threshold. The fact that it didn’t trigger any alarms is deeply concerning. The process to claw back that $2.3 million will be politically and logistically delicate. First, the scholarship-administering organizations must formally notify each of the 299 families of the overage. Then, they’ll have to work to either freeze the excess funds or directly debit the accounts. It’s a painstaking, account-by-account process to rectify a mistake that should have been prevented by basic digital safeguards in the first place.

Senator Gaetz’s proposed legislation shortens the window for recouping inactive funds from two years to one. Beyond the “positive” revenue impact, how will this change affect families using the program, and what are the detailed mechanics of alerting parents before their funds are reclaimed?

This change significantly increases the pressure on families. Shortening the window from two years to one means parents can’t let funds sit for long-term planning without risking forfeiture. For the state, it’s a win; a Senate analysis projects a “positive” fiscal impact because money is returned to state coffers much faster. To implement this, the scholarship organizations would need to create a robust notification system. I imagine a series of automated alerts—emails, texts, and certified letters—would begin several months before the one-year deadline, explicitly warning parents that their funds are about to be reclaimed. It’s a move toward tighter financial control, but it could penalize families who are less organized or are trying to save for a significant educational investment down the road.

What is your forecast for the future of Florida’s school choice voucher program as lawmakers attempt to balance expansion with these significant financial and oversight challenges?

My forecast is that we are entering an era of course correction. The ideological push for universal school choice has outpaced the administrative capacity to manage it responsibly, and these audit findings are the inevitable result. Lawmakers simply cannot ignore a $47 million shortfall or $400 million in dormant funds. Moving forward, I expect to see legislation, like the bill sponsored by Senator Gaetz, that imposes much stricter guardrails: mandatory enrollment verification, hard-and-fast caps on account balances, and quicker reclamation of inactive funds. The core of the program will survive because the political will is there, but its days of unchecked growth are over. The new focus will be on building an infrastructure of accountability to ensure that taxpayer money is actually, and verifiably, spent on educating children.