As we dive into the recent decision by the Federal Communications Commission to end federal funding for Wi-Fi hotspots and internet access on school buses through the E-Rate program, we’re joined by Donald Gainsborough, a political savant and leader in policy and legislation at the helm of Government Curated. With his deep expertise in telecommunications policy and federal funding initiatives, Donald offers a unique perspective on how these changes impact education and broadband access. In this interview, we explore the origins and evolution of the E-Rate program, the rationale behind the FCC’s controversial decision, concerns over misuse of resources, the split opinions among commissioners, and the broader implications for students and communities still grappling with the digital divide.

Can you walk us through what the E-Rate program is and how it has historically supported schools and libraries?

Absolutely, Debora. The E-Rate program, established under the Telecommunications Act of 1996, is a federal initiative designed to provide discounts on internet access and telecommunications services to schools and libraries, particularly those in underserved areas. It’s funded through the Universal Service Fund, which helps ensure that these institutions can afford the connectivity needed for modern education. Typically, E-Rate covers things like high-speed internet, internal networking equipment, and related services that directly enhance learning environments. Over the years, it’s been a lifeline for bridging the digital divide, ensuring students and patrons have access to essential online resources right within classrooms and library spaces.

How did the E-Rate program adapt during the COVID-19 pandemic to address new connectivity challenges?

During the pandemic, when schools shut down and learning shifted online, the digital divide became glaringly obvious. Many students lacked reliable internet at home, so the FCC expanded E-Rate to fund Wi-Fi hotspots that schools and libraries could loan out to families. They also allowed funding for Wi-Fi on school buses, turning them into mobile connectivity hubs for students in rural or low-income areas who might be commuting long distances. This was a creative, emergency-driven response to keep education accessible when traditional classroom settings weren’t an option, and it continued even after the public health crisis eased.

What prompted the FCC to reverse course and end funding for Wi-Fi on school buses and hotspot loan programs?

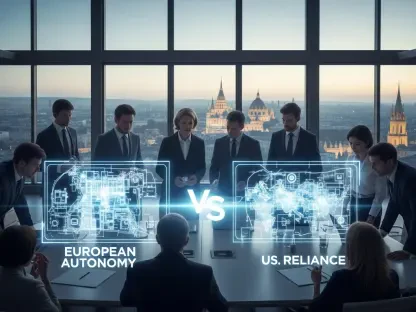

The decision, led by FCC Chair Brendan Carr, hinges on a strict interpretation of the law. Carr argued that the E-Rate program’s mandate is narrowly defined to support connectivity within classrooms and libraries—physical spaces explicitly mentioned in the Communications Act. He and others felt that extending funds to school buses or off-site hotspots was an overreach by the previous administration, going beyond what Congress intended. Essentially, they saw it as a misuse of authority, labeling it unlawful because it didn’t align with the program’s original statutory boundaries.

Can you elaborate on the safety concerns raised about providing internet access on school buses?

Certainly. One of the key arguments against Wi-Fi on school buses was about child safety and parental oversight. Critics, including Chair Carr, pointed out that buses are unsupervised environments compared to classrooms. They worried that kids could access harmful or inappropriate content without proper monitoring. There’s also the concern that parents lose control over when and how their children engage with the internet in such settings. It’s a valid debate—balancing connectivity needs with the responsibility to protect young, impressionable users from online risks.

There were also issues raised about the misuse of Wi-Fi hotspots. What can you tell us about that aspect of the decision?

Yes, another sticking point was the alleged waste associated with hotspot loan programs. Chair Carr claimed that many of these devices, funded by E-Rate, were quickly lost or stolen, leading to millions of dollars down the drain. The argument is that without tight accountability measures, taxpayer money was being squandered on equipment that didn’t always serve its intended educational purpose. However, specific data or evidence to quantify this loss wasn’t widely detailed in public statements, which has left some skepticism about the scale of the problem.

How did the FCC commissioners split on this decision, and what were the main points of disagreement?

The vote was 2-1, with Chair Carr and Commissioner Olivia Trusty supporting the end of funding, while Commissioner Anna Gomez dissented. Gomez argued that cutting these programs undermines efforts to close the digital divide, especially post-pandemic when connectivity remains a barrier for many students. She emphasized the practical benefits these initiatives provided, suggesting that the decision prioritized legal technicalities over real-world needs. It highlights a deeper tension within the FCC about the scope of E-Rate and how far it should stretch to address broader societal challenges.

What has been the response from advocates who supported keeping these connectivity programs in place?

The backlash has been significant. The American Library Association, for instance, called the decision a step backward, arguing that hotspot lending—something libraries have done for a decade—has been transformative for people in crisis or without home internet. Their president criticized the lack of due process, meaning there wasn’t enough time for stakeholders to weigh in before the vote. Similarly, leaders from nonprofit groups focused on broadband equity described the move as detrimental to students and lifelong learners, warning that it widens the homework gap and leaves communities less prepared for a digital future.

Why do you think these programs are seen as so critical, especially in the aftermath of the COVID-19 crisis?

The pandemic laid bare how essential internet access is for education and beyond. Many students couldn’t participate in remote learning without reliable connectivity, and programs like hotspot lending and bus Wi-Fi became stopgap solutions for those without other options. Advocates argue that these initiatives aren’t just about homework—they enable telemedicine, job searches, and basic digital participation. For rural or low-income families, losing this support means falling further behind in a world where being online isn’t optional anymore. It’s about equity as much as it’s about education.

What is your forecast for the future of broadband access initiatives in education given this rollback?

I think we’re at a crossroads, Debora. On one hand, this decision might push policymakers to seek alternative funding mechanisms or programs specifically designed for off-site connectivity, rather than stretching E-Rate beyond its original intent. On the other, it could galvanize advocates and lawmakers to revisit and clarify the legal framework around E-Rate to explicitly include such uses. The digital divide isn’t going away, and public pressure will likely keep driving innovation in how we fund access. But without a unified vision at the federal level, we risk patchwork solutions that leave too many students disconnected. I expect heated debates in Congress and possibly new legislation in the coming years to address these gaps head-on.