The unassuming lampposts and traffic signals lining suburban streets now house a powerful, interconnected surveillance network capable of tracking the daily movements of millions of citizens. In Scottsdale, Arizona, the police department’s intensive use of this technology has placed the city at the center of a national debate, pitting the stated goals of public safety against fundamental privacy rights. Recent data reveals the Scottsdale Police Department (PD) has become a superuser of a sprawling automated license plate reader (ALPR) system, conducting a volume of searches that rivals statewide agencies and raises profound questions about the future of warrantless surveillance in American communities.

The Digital Dragnet: Understanding Flock Safety’s Nationwide Network

At the heart of this industry shift is Flock Safety, a company that has redefined surveillance with its network of AI-powered ALPR cameras. This system is not a collection of isolated devices but a vast, interconnected web linking more than 5,000 communities across the United States. With a reported 80,000 cameras capturing vehicle data, the architecture of Flock’s network allows for the near-instantaneous sharing of information, creating a digital dragnet of unprecedented scale.

The company has successfully positioned itself as a modern, Silicon Valley-style solution for security, attracting a diverse clientele that extends far beyond traditional law enforcement. While police departments remain primary customers, Flock also markets its technology to private entities, including large retailers like Lowe’s and Home Depot, as well as thousands of homeowner associations. This expansion into the private sector effectively blurs the line between public and private surveillance, creating a pervasive system where data collected in a residential neighborhood can be accessed by law enforcement agencies hundreds of miles away.

The technological influence of this model stems from what civil liberties advocates describe as an aggressive nationwide data-sharing agreement. When a police department partners with Flock, it effectively agrees to pool its localized vehicle data into a national database. This arrangement grants thousands of law enforcement and private users access to the sensitive driving patterns of local residents, amplifying the potential for tracking individuals far beyond the jurisdiction where the data was initially collected.

Scottsdale’s Watchful Eye: A Data-Driven Deep Dive

An Unprecedented Surveillance Footprint

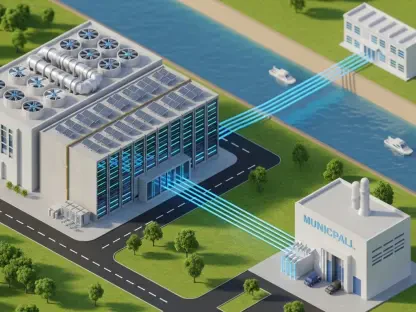

The Scottsdale Police Department has fully integrated ALPR technology into its core operational strategy, making it a central component of its public safety initiatives. The department leverages real-time data from the Flock network within its advanced Real-Time Crime Center (RTCC) and its Drone as a First Responder (DFR) program. This integration allows for a dynamic and immediate response, providing field officers with critical information during active investigations and in-progress calls.

Law enforcement officials justify this high level of adoption by pointing to its effectiveness as a market driver for enhanced public safety. According to a department spokesperson, the technology provides timely intelligence that is crucial for identifying suspects, locating vehicles involved in criminal activity, and efficiently resolving cases related to property crimes, assaults, and other serious offenses. To mitigate concerns of overreach, Scottsdale PD reports it has internal safeguards, including requirements for a valid case number for all searches and supervisor oversight to ensure compliance with departmental policy.

By the Numbers: Quantifying the Search Volume

Data covering a period from late 2024 to mid-2025 provides a stark illustration of Scottsdale’s intensive use of the system. During this timeframe, the department conducted 12,527 searches of the ALPR database, a figure that highlights its position as a power user of the technology.

This search volume is particularly significant when placed in a statewide context. Scottsdale’s queries accounted for approximately 22% of all searches conducted by Arizona agencies within the analyzed dataset, a number that nearly equals the activity of the Arizona Department of Public Safety (DPS), the statewide agency responsible for patrolling all highways. This forward-looking perspective, derived from historical data, offers a crucial window into the rapid and deep integration of mass surveillance tools by municipal police forces.

Cracks in the System: Misuse, Flaws, and Broken Trust

Despite its rapid adoption, the ALPR industry is confronting significant technological and ethical obstacles that challenge its integrity. Documented cases of misuse have surfaced across the country, including reports of police in Texas using an ALPR system to track a woman who traveled out of state for a legal abortion. In another instance, the Glendale Police Department in Arizona was found to have employed a discriminatory slur while searching the very same database, revealing the potential for the technology to be wielded for ideological or biased purposes.

Beyond intentional misuse, the system’s security has been called into question. Researchers have identified significant vulnerabilities, such as Flock cameras being exposed to the open internet without requiring login credentials, which could allow unauthorized access to live vehicle tracking data. While the company has often dismissed such reports as theoretical, the Scottsdale PD acknowledged its awareness of a potential compromise, though it found no evidence its own data was breached. These security flaws undermine public trust and the foundational promise of a secure system.

Further complicating the landscape are discrepancies between corporate policies and reported practices. Flock Safety has publicly stated it does not share data with federal agencies like U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). However, independent reporting has indicated otherwise, creating a credibility gap that fuels skepticism about the company’s commitment to its own data-sharing guidelines and raises questions about the true extent of data dissemination.

Policing the Police: The Legislative Battle Over Surveillance

The current regulatory landscape surrounding ALPR technology remains fragmented and contested. In Arizona, proposed legislation backed by law enforcement has drawn criticism from privacy advocates who argue it does more to restrict public access to collected data than to limit how police can use the technology. This approach stands in sharp contrast to the more privacy-protective laws enacted in other states.

For example, states like New Hampshire and Virginia have implemented stricter regulations that directly address the core privacy risk of long-term data retention. New Hampshire’s law mandates that any ALPR data not associated with a crime or a hotlist must be deleted within three minutes, striking a balance that allows for immediate investigative alerts without creating a permanent, searchable history of innocent citizens’ movements. These contrasting legislative models highlight a national divide over how to regulate powerful surveillance tools.

Within police departments, the effectiveness of internal safeguards remains a key point of contention. While agencies like Scottsdale PD assert that policies requiring case numbers and supervisor approval are sufficient to prevent abuse, critics argue these measures are inadequate. Without independent, external oversight and robust legislative guardrails, compliance becomes a matter of internal discretion, leaving the system vulnerable to the same patterns of misuse and error seen in other jurisdictions.

A Rising Tide of Resistance: The Bipartisan Push for Privacy

The future trajectory of surveillance technology adoption is increasingly shaped by a growing public and political opposition that spans the ideological spectrum. Concerns over warrantless government tracking have created a rare non-partisan alliance, with prominent figures from both major political parties voicing support for stricter limitations on this technology.

This sentiment is manifesting in tangible resistance at the local level, acting as a market disruptor to the industry’s expansion. In Arizona, municipalities such as Flagstaff and Sedona have canceled their contracts with Flock Safety, signaling a shift in how communities weigh the perceived benefits of ALPR systems against their societal costs. This trend of local government pushback indicates that the market for mass surveillance is not without its limits.

The debate is also escalating in the legal arena, with ongoing constitutional challenges questioning whether continuous, warrantless tracking of a person’s movements violates the Fourth Amendment. This legal pressure, combined with the grassroots movement for privacy, suggests a future where the unchecked proliferation of surveillance technology will face significant hurdles, forcing a reevaluation of its place in a free society.

Balancing the Scales: Security Needs vs. Civil Liberties

The widespread deployment of AI-powered surveillance has placed law enforcement’s pursuit of public safety in direct conflict with the fundamental right to privacy. The case of Scottsdale’s intensive ALPR usage encapsulates this modern dilemma, where a tool promoted for its crime-solving efficiency simultaneously creates a mechanism for the mass collection of data on innocent individuals. The societal implications of this technology, operating without robust and transparent oversight, have become a defining issue for communities across the nation.

The industry’s rapid growth has outpaced both legislative and judicial review, leaving a regulatory vacuum that favors data collection over individual liberties. This period highlights a critical need for a societal reevaluation of the balance between security and freedom in an era increasingly defined by data. The events in Arizona and elsewhere serve as a clear signal that the path forward requires not just technological innovation, but a renewed commitment to the principles of privacy and accountability.