With an unprecedented multi-billion-dollar federal investment flowing into broadband infrastructure, the prevailing narrative suggests that the end of the digital divide is finally within sight, promising a future where every American household is connected. However, this focus on physical networks masks a more persistent and complex challenge that wires alone cannot solve. A growing body of research and expert analysis reveals that the most significant barriers to digital equity are not technological but human. Even with universal access to high-speed internet, millions of individuals remain functionally disconnected due to a lack of essential digital skills and a deep-seated distrust of the online world. This report examines the evolution of the digital divide, moving beyond the metrics of network deployment to explore the critical human elements that will ultimately determine the success or failure of the nation’s connectivity goals. As policymakers and industry leaders celebrate the rollout of new fiber lines, they must confront the reality that true digital inclusion requires a profound investment in people.

Beyond the Broadband Map: Redefining Digital Inequity Today

The contemporary understanding of the digital divide is undergoing a fundamental transformation. For decades, the problem was framed almost exclusively as an infrastructure deficit, a gap measurable on a map by highlighting areas without access to broadband cables. Today, that framework is proving inadequate. The new frontier of digital inequity lies not in the physical distance between a home and a fiber optic line but in the human capacity to use that connection meaningfully, safely, and effectively. This shift redefines the challenge from a simple engineering problem to a complex socioeconomic issue rooted in education, confidence, and trust.

At the heart of this new paradigm are two critical components that have been historically undervalued in policy discussions: digital skills and trust. Digital literacy is no longer a niche competency but a foundational skill essential for economic participation, civic engagement, and access to basic services like healthcare and education. It encompasses a wide spectrum of abilities, from operating a device to navigating complex software, discerning misinformation, and protecting personal data online. Simultaneously, trust acts as the gateway to digital adoption. Widespread concerns over data privacy, cybersecurity threats, and online scams create a powerful deterrent, particularly for vulnerable populations, rendering even the fastest internet connection useless if people are too afraid to use it.

This evolving perspective is being championed by leading policy experts and institutions that are reshaping the national conversation around digital equity. Analysts from organizations like the Brookings Institution are urging a pivot from a supply-side focus on infrastructure to a more balanced, demand-side approach that empowers end-users. Their research underscores a crucial oversight in current strategies: the assumption that availability automatically translates to adoption and meaningful use. By centering the experiences and needs of individuals, these thought leaders are advocating for a more holistic strategy, one where investments in digital literacy programs and trust-building initiatives are given the same priority as the deployment of physical networks.

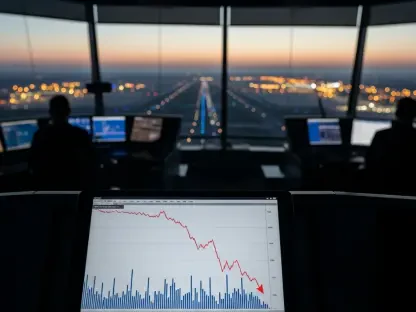

The Shifting Dynamics of Digital Access

The Rise of the Digitally Invisible: Identifying Who Is Truly Left Behind

Beyond the familiar image of isolated rural communities waiting for broadband, a more subtle and pervasive form of exclusion has emerged: the “digitally invisible.” This concept describes a diverse population whose lack of engagement with the digital world makes their presence “nearly quiet” in datasets, policy considerations, and the design of new technologies. These individuals are not necessarily living in areas without internet service; rather, they are rendered invisible by barriers such as outdated skills, inadequate equipment, or a fundamental lack of confidence in their ability to navigate the online environment. Their invisibility creates a vicious cycle, as their needs are overlooked when new digital services and platforms are developed, further deepening their exclusion.

The demographics of the digitally invisible are far broader and more complex than traditionally assumed. While the group certainly includes residents of remote agricultural regions, it also encompasses a significant number of people in fully connected urban and suburban areas. This includes older adults who may lack the training to use modern devices, low-income families who cannot afford up-to-date hardware or software, and even mid-career professionals whose skills have not kept pace with rapid technological change. An office worker using obsolete equipment or an employee untrained in contemporary workflow tools is just as much a part of this group as a farmer without a fiber connection, as both are unable to participate fully in the modern economy.

This problem is being amplified by the rapid integration of artificial intelligence into daily life and work. As AI-powered tools become standard in various professions, from analytics to creative design, they are creating a new and formidable barrier to entry. Those who lack the foundational digital literacy to understand and harness these technologies risk being left behind at an accelerated rate. This creates a new form of digital disadvantage where the gap is not between the connected and the unconnected, but between those who can leverage AI to enhance their productivity and opportunities and those who cannot. The rise of AI makes the need for proactive and inclusive digital skills training more urgent than ever before.

From Infrastructure Billions to Human Investment: A Pivotal Funding Opportunity

The centerpiece of the federal government’s strategy to close the digital divide is the $42 billion Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) program. This historic investment is primarily directed at the program’s core mission: funding the planning, deployment, and adoption of high-speed internet infrastructure in areas of the country that are unserved or underserved. While essential for building the nation’s foundational connectivity, the program’s heavy emphasis on physical assets risks overlooking the equally critical human elements of the digital divide. The success of BEAD hinges not just on how many miles of fiber are laid but on whether people have the skills and confidence to use the connections that are built.

As states proceed with their implementation of BEAD-funded projects, projections indicate a strong possibility of surplus funds remaining after the primary infrastructure objectives are met. This potential reallocation presents a landmark opportunity to pivot toward a more balanced and effective national strategy. These funds could be directed to digital equity initiatives that have historically been underfunded, such as community-based digital literacy training, public awareness campaigns on cybersecurity, and programs providing affordable devices. Such a shift would move policy beyond the narrow focus on network construction and toward a more comprehensive vision of digital inclusion that addresses the full spectrum of barriers people face.

This potential funding pivot offers a chance to create a more resilient and holistic national strategy that integrates infrastructure development with human capital investment. By treating digital skills and trust-building as co-equal priorities alongside network deployment, policymakers can ensure that the massive investment in broadband yields its intended social and economic returns. A forward-looking approach would see states leveraging these funds to build sustainable ecosystems of support, partnering with libraries, schools, and non-profits to deliver localized training and resources. This would finally align federal investment with the reality that a connection is only valuable when people are empowered to use it.

The Human Barriers: Why a Connection Alone Is Not Enough

The persistent challenge of the digital divide demonstrates that the availability of high-speed internet does not automatically guarantee its use. Even in areas with robust broadband infrastructure, significant segments of the population remain offline or underutilize their connections due to a complex web of human-centric barriers. These obstacles include a lack of digital skills, fear of online threats, the perceived irrelevance of the internet to daily life, and the high cost of devices and services. These issues persist because they are rooted in individual circumstances, educational backgrounds, and personal experiences, factors that cannot be addressed by simply deploying more fiber optic cable.

For years, many policies have operated on the flawed assumption that infrastructure is a panacea. This “build it and they will come” approach has led to disappointing adoption rates in many newly connected communities, revealing a fundamental misunderstanding of the problem. Treating the digital divide as a purely technical issue ignores the essential need for concurrent investment in human empowerment. Without parallel efforts to teach people how to navigate the digital world safely and effectively, even the most advanced networks will fail to bridge the equity gap. This policy failure highlights the necessity of moving away from siloed thinking and toward a more integrated model.

To create true digital equity, strategies must be developed that simultaneously invest in infrastructure, skills, and public trust. An integrated approach would involve weaving digital literacy components into infrastructure grant requirements, ensuring that community engagement and training are part of every deployment project. It would mean funding public-private partnerships to create ongoing educational programs and cybersecurity resources that build consumer confidence. By tackling these challenges in parallel, policymakers can create a virtuous cycle where accessible infrastructure encourages skill development, and increased skills and trust drive demand for and meaningful use of that infrastructure.

Policy in Flux: Navigating the Legislative Landscape of Digital Equity

The federal government’s approach to closing the digital divide is currently shaped by two landmark pieces of legislation: the Broadband Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) program and the Digital Equity Act. While BEAD allocates its massive $42 billion budget primarily to the deployment of physical networks, the Digital Equity Act focuses specifically on the human side of the equation, providing grants for digital literacy training, technology access, and other initiatives aimed at empowering people. Together, these programs represent a comprehensive, two-pronged strategy, yet their implementation and funding have exposed a historical tension in policymaking.

This legislative landscape is the product of what experts describe as a “ping pong of support” between funding for infrastructure and funding for people-centric programs. Over the past several decades, federal priorities have often oscillated between these two poles rather than pursuing them as integrated, co-dependent goals. For example, the Trump administration’s move to eliminate funding for grants under the Digital Equity Act highlighted the vulnerability of skills-based programs, which are often seen as secondary to the more tangible work of network construction. This inconsistent support has hampered the development of long-term, sustainable initiatives for digital literacy and inclusion, creating an environment of uncertainty for the community organizations doing this essential work.

The success of the current national strategy will ultimately depend on how these federal initiatives are implemented at the state level. State broadband offices and digital equity planners are now tasked with translating broad federal mandates into effective, localized programs. Their implementation plans offer a critical opportunity to create a more balanced and holistic approach, braiding together BEAD and Digital Equity Act funding to support projects that build networks and user capacity in tandem. This state-level execution is where the policy vision will meet the on-the-ground reality, determining whether the nation’s historic investment will finally address the digital divide in all its dimensions.

Forging an Inclusive Future: A New Mandate for Technology and Policy

The next frontier of digital equity will be defined by the rise of emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence. As AI becomes more deeply integrated into the economy and society, it holds the potential to either dramatically narrow or dangerously widen existing divides. AI-driven platforms can offer personalized learning, automate complex tasks, and increase access to information for some, but for those lacking foundational digital skills, they will become another insurmountable barrier. The ability to effectively prompt an AI, interpret its outputs, and understand its limitations is rapidly becoming a critical form of literacy. Without proactive intervention, only those who “truly know how to harness it will benefit,” creating a new class of digital disadvantage.

This reality places a new and urgent mandate on policymakers and technology leaders to design and deploy technology with inclusivity at its core from the very beginning. It is no longer sufficient to build a powerful new tool and hope that society will adapt to it. Instead, leaders must proactively consider who is being left out and design solutions that are accessible, intuitive, and beneficial to all users, regardless of their technical expertise. This requires a shift from a technology-first mindset to a human-centered one, where the development process includes diverse user testing, accessible design principles, and a clear understanding of the real-world contexts in which these tools will be used.

To ensure that technological advancement promotes equity rather than exacerbating division, leaders must begin asking a different set of questions. Before launching any new application or digital service, they must critically assess its accessibility. Key questions include: How will people get to this technology? Have we considered not just the application itself, but the extent to which people have the tools, skills, and resources to connect in meaningful ways? Is this technology designed to serve those with the lowest levels of digital literacy, or does it assume a high degree of pre-existing knowledge? By embedding these questions into the innovation lifecycle, government and industry can begin to forge a more inclusive digital future where technology serves as a bridge, not a barrier.

The Path Forward: A Call for a Human-Centered Digital Strategy

The central argument that emerged was clear: achieving true digital equity demanded a multifaceted approach that valued investment in people as much as investment in infrastructure. The debate had definitively shifted from a narrow focus on network maps and broadband speeds to a more sophisticated understanding of the human barriers—skills, trust, and affordability—that keep millions of Americans from participating fully in the digital world. This recognition marked a critical turning point, challenging the long-held assumption that physical connectivity alone could solve the problem.

In response, a call to action was issued for government and industry stakeholders to fundamentally break their outdated assumptions about the digital divide. The conversation moved beyond the simplistic binary of the “haves and have-nots” to acknowledge the nuanced reality of the “digitally invisible”—individuals who may have a connection but lack the capacity to use it. This required policymakers and corporate leaders to look past their spreadsheets and engage directly with the communities they aimed to serve, listening to their fears, understanding their needs, and co-designing solutions that built both networks and confidence.

Ultimately, the blueprint for a more inclusive digital future was laid out, centered on a renewed commitment to human-centered design and policy. Recommendations coalesced around three core pillars: investing in sustainable, community-based digital literacy programs; fostering trust through robust cybersecurity education and consumer protections; and ensuring that emerging technologies like AI were developed and deployed with accessibility as a primary goal. It became evident that building a society where technology served everyone was not merely a technical challenge but a moral and economic imperative.